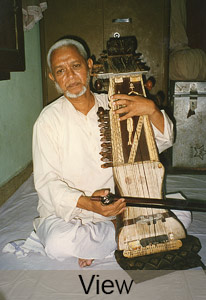

Ustad Mohammed Ali Khan was a rare sarangi player, an eccentric musicians' musician. I met him in 1997 at a lunch feast at the house of Ghulam Sabir in Delhi. He modestly invited me to his house in Old Delhi, saying he could show me a thing or two. Did he ever! His house is (it should be) a pilgrimage place for sarangi players—the haweli of the great Mamman Khan, the ustad (teacher) and father-in-law of the immortal Bundu Khan. Mohammad Ali Khan was the grandson of Kale Khan who was one of Mamman Khan's three brothers. As a child he had spent a lot of time listening to Bundu Khan's sarangi and his "jute-wute kahaniya"—crazy untrue stories.

He had had a stroke several years before I met him, so was another sarangi player who was not 16-annas-to-the-rupee. But this made for fantastic teaching. He would sit for hours yelling tans at me, trying to plant Bundu Khan's tan style in my brain. He also taught me many complex paltas, note perrmutation exercises which were a speciality of his family. One day he reached under his bed and produced an ancient diary in which he had written 1001 paltas, mostly long and complex. He bundled us into a riksha, and we went off to photocopy it for me. This book is a masterpiece of stream-of-consciousness musical thinking. I have since analysed it and found that, although they are organised extremely randomly and illogically, after standardising them so that the lowest note of the first-position palta is Sa and so they are all in the same scale, there are still over 800 unique paltas amongst them. My paper "Paltas: maps of tonal space" which analyses many aspects of the palta phemomenon will eventually be published on this site.

Mohammed Ali Khan was a player of the sursagar, a sort of giant sarangi that also had a top-course of melodic strings that could be plucked like a swarmandal, and also some chikari strings running along the side of the fingerboard which he plucked with his little finger between bowed melody notes. He had not owned a sarangi for many years, and his sursagar was in a terrible state of repair. Two of the bone bridges, having been broken, had been replaced with cast aluminium bridges, and there was a generally chaotic feel to the way that the instrument's many strings and bridges were laid out.

In our lessons he would usually sing, or we would pass my sarangi back and forth. His neurological condition was such that sometimes his playing was embarrassing—but other times I felt I was sitting in the same room as Bundu Khan. He was a master of Bundu Khan's unique fingering techniques which often involved the rapid alternation of two fingers, similar to sitar usage.

Our lessons, if in the morning, were exhausting, but his wife would often terminate them, bringing in a huge pile of roties and the most delicious mutton curry I've ever tasted. He was also teaching his grandson Jaavad on the violin—mostly paltas—screeching away very fast and totally out-of-tune. I respectfully asked him "don't you think he should pay some attention to intonation?" He said "no no that will come of its own accord". I am curious whether it has indeed come for Jaavad.

Mohammed Ali Khan was hard of hearing, and he had a terrible hearing aid, purchased on some streetcorner for fifty rupies. It just rang and echoed in his ear, so he kept it turned off. One day I collected a highly-respected ear doctor from New Delhi and dragged him to his house in Sui Walan on a riksha. She seemed like she'd never been on a riksha before, certainly never in Old Delhi. She was more than a little nervous. When we arrived, Mohammed Ali Khan implored her to have lunch (she was a Hindu vegetarian) and when she wouldn't have that, forced tea and chaklis on her. She was desparate to test his ears and escape. Anyway I delivered his new high-tech hearing aid a week later. Over the coming weeks I noticed that he wasn't using it. The truth of the matter was that he kept it turned off so that he wouldn't have to listen to his wife's nagging. What a man! I really loved him.

.jpg) Several years after Mohammed Ali Khan's passing away in 2002, I purchased his sursagar from his wife. It is huge and extremely heavy. I nearly died sitting in the July sun in Delhi waiting for some carpenters to build a coffin in which to send it back to Bombay, where I was staying in 2006. In Bombay, I abandoned the coffin and brought the sursagar back to the UK in a giant cricket bag. It sat idle for a few years before I had the courage to violate its chaotic sanctity and repair it. I spent much of the summer of 2013 totally renovating it, making all new bridges, making it a beautiful and very playable instrument. It has a profoundly ethereal and introverted sound—perfect for dhrupad.

Several years after Mohammed Ali Khan's passing away in 2002, I purchased his sursagar from his wife. It is huge and extremely heavy. I nearly died sitting in the July sun in Delhi waiting for some carpenters to build a coffin in which to send it back to Bombay, where I was staying in 2006. In Bombay, I abandoned the coffin and brought the sursagar back to the UK in a giant cricket bag. It sat idle for a few years before I had the courage to violate its chaotic sanctity and repair it. I spent much of the summer of 2013 totally renovating it, making all new bridges, making it a beautiful and very playable instrument. It has a profoundly ethereal and introverted sound—perfect for dhrupad.

Most of the videos here are of our lessons, but there are some of him playing his sursagar or my sarangi or just talking. The first set here is from May 31, 1997. This gives some idea of his style of being: he moves rapidly between teaching me various bandishes, performing on the sursagar, and talking about music and life. It was exhausting. He had much more energy than I had—not at all phased by the intense heat of Delhi at the hight of summer. The first video is of various bandishes in Bhairav including a gorgeous tarana composition:

Now we have some explanations of bandishes in Darbari interspersed with some beautiful sursagar playing on the same day. The gestalt of Bundu Khan's Darbari shines through, and you can see some of the unusual fingering techniques of this tradition:

Then he played rag Jaitashri on the sursagar:

Followed by rag Chandani Kedar—again very close to Bundu Khan's style:

Here we see Mohammed Ali Khan teaching me tans, supervising my tan practice in Bhairav. This was one of his early attempts to extract the relentless circular tans of this style out of me. Not great to listen to—I was hot and tired and the instrument was out of tune, but this gives some idea of his teaching style and of his conception of non-stop tan generation.

Our next offering is from earlier, even longer, session on Bhairav tans on May 28, 1997. In this sesion we passed my sarangi back and forth. It must be emphasised that for decades he had not had a sarangi in the house, so he was entirely unused to the shorter (than the sursagar's) intervals.

That ended with a discussion of Bundu Khan's technique of repeating notes by rapid alternation of three fingers on the same note. One use of this technique was for the andolan in Darbari. Then there's a short but lucid demonatration of Darbari on my sarangi:

I visited Mohammed Ali Khan on the 3rd of June, 1997. We began with rag Bhairav and a wonderful bandish ki thumri in Bhairav.

This was followed by the rare rag Sogan. Most of the music and conversation n the following clip is drowned out by an insanely loud electronic swarpeti— a raw square-wave generator, but I have kept the clip for a couple of enlightening sequences in which the Ustad demonstrates Sogan on my sarangi.

Thankfully, the tape ended, and it seams that while changing the tape, I also reduced the volume of the swarpeti. More rag Sogan:

After that Mohammed Ali Khan moved on to Bilaval Bahar, which started as something akin to Alhaiya Bilaval and then morfed briefly into Jaijaivanti Bahar.

When I asked him if he had started on Alhaiya Bilaval, he then moved onto some concerted fucus on Alhaiya Bilaval:

Our next meeting was on the 6th of June. We began with Alhaiya Bilaval, again in passing-sarangi-back-and-forth mode. A young flute player had arrived for a lesson and was waiting patiently.

When it came time for the flute player to play, I offered him my seat but he declined, chosing to sit behind the Ustad. He played Yaman and Mohammed Ali Khan ignored him. He left, and we see the Ustad's son enjoying himself feeding his own toddler.

Then we worked on Yaman, mostly paltas and tan formation:

The day ended with rag Malkauns:

Two days later, on the 8th of June, we began with a session in Bhairavi. Mohammed Ali Khan was largely pre-occupoied with transmitting a bandish ki thumri in rag Bhairavi, but also explored chromatic tan formation:

Then his son Ahmed Ali played some Bhairavi on the sitar, largely ignored by his father.

We moved on to rag Jaunpuri, in which Mohammed Ali Khan also had a bandish he wanted to teach me:

We returned to Bhairavi, and Mohammed Ali Khan repeated the words of the bandish he had taught me earlier—for the more linguistically atuned ears of my partner Lalita du Perron.

After this Mohammed Ali Khan unearthed some audio cassettes of his playing the sursagar decades earlier, before his stroke and played them for us. The sound quality wasn't great, but at moments they give a glimpse of his former glory. Unfortunately the chaos intrinsic in sursagar technique rather mirrors the stream of consciousness musical experience that I already knew too well from sitting with him. Bowing the melody, plucking some of the melody on the metal svarmandal-like strings, and strumming the chikari strings—does not combine to create very coherent music, but its ethereal, nearly psychedelic, intensity cannot be denied. First we hear a recording of rag Desh. This is followed by a radio recording os Shri rag that is introduced with a survey of Mohammed Ali Khan's ancestor's and teachers: his grandfather Kale Khan, the great Bundu Khan, his father Mammu Khan, his relative the vocalist Chand Khan who was still his neighbour across the haweli courtyard when I was there. The recording ends with rapturous applause. I think it was probably I live recording of the Delhi Akachvani Sangeet Samelan.

The next three recordings are from June 13, 1997. In the first he teaches me rag Shankara. He begins with teaching a vilambit bandish. We both move back and forth between singing and sarangi. After various upaj, we went on to a drut bandish. As in many of our sittings, we spent a lot of time on his dictating the words of the songs while I wrote.

The electricity went off, so now we have some atmospheric but very black film. We continued with Shri rag . After the lights came back on, we pursued more tans.

This was followed by tans in Yaman.

I returned on June 15th. We began with rag Bhupali, starting with dictation of the text of a bandish:

Then rag Pilu—Mohammed Ali Khan sang and demonstrated a wonderful bandish ki thumri in Pilu:

Our next meeting was on the 18th of June. We worked a long time on rag Bageshri, but the first tape deteriorated befor I could digitise it. Here we are continuing —first he tought me the text of a vilambit bandish and played it beautifully on sarangi accompanied by the tabla machine.

Next was rag Kedar. He started with teaching me a very unconventional aroha-avroha (ascending and descending scale). The Ustad's sarangi playing was very reminiscent of Bundu Khan's immortal recording in this beautiful rag. The session ended with our listening together to Bundu Khan's recording of rag Miyanki Malhar.

Next we practised rag Puriya, starting with the text of a vilambit bandish, followed my more practice with the

tabla machine.

Then Mohammed Ali Khan interrogated me about the tonal material of Miyanki Malhar then demonstrated Miyanki Malhar on sarangi, followed by returning to Puriya, mostly tans, with a tabla machine:

The next clip is from a visit to the home of Mohammed Ali Khan's vocal student Shabani. She sings rag Shankara:

During this period Mohammed Ali Khan became more and more habituated to playing my sarangi. He seemed to enjoy it immensely, though he had resolved, with considerable bittermess, to leave sarangi completely and had for years refused to teach sarangi players. Through the month of June, his playing became more consisitently exquisite and tuneful. Viewing the videos now (2025), I am struck by how unwaveringly relaxed his left hand appears. I know from my own practice that whenevr I feel, perhaps because of being out of practice, a danger of going out of tune, I tend to tense up and try to make my hand behave. I don't think Mohammed Ali Khan had ever done this. His hand was eminently relaxed and its positioning never changed—he trusted in his mind to arrive at the correct notes, believing that he couldn't influence this by bodily exertion. And repeated exposure during this period made him more successful at taming the sarangi.

On the 25th of June we had a long and particularly tranquil and tuneful session, beginning with rag Multani, which he played beautifully. He also taught me three bandishes, as usual first dictating the texts for me to write.

We went on to Bahar.

There was an interval of a lovely demonstration of Jaijaivanti, and also a bandish ki thumri (hori) in Kafi. The session ended with more tans in Bahar and Yaman, and intensive technical instruction of paltas and fingering and bowing techniques includin his amazing percussive use of a very angled upbow.

The day ended with a not very attentive esraj lesson in rag Bhairav to a boy who was Bundu Khan's sister's grandson:

On the 27th I did not take my sarangi to his house. He re-acquainted himself with his sursagar. First a long examination of rag Bhimpalasi in the course of which he taught me three bandishes. On occasion he passed me his sursagar and I had to sink or swim negotiationg the playing string's much greater length.

Then he changed his attention to rag Bihag, but for a while switched back to Bhimpalasi whwn I asked him to play a bandish that he had taught me earlier. Then he returned to Bihag for the rest of the sitting:

On the 24th of August we had a long gruelling session which mostly focused on tan formation in Bhairav. During this sitting Mohammed ali Khan demonstarted both on my sarangi and on his grandson's violin, which he held vertically in front of him, somehow transferring his sarangi technique: The video ends with an uninspiring sequence of his grandson practising scales on the harmonium.

Two days later, we began with rag Desi. To begin with Mohammed Ali Khan played harmonium and sang. As well as barhat and tans, we covered two famous bandishes.

Next was rag Desh. Here the Ustad played sarangi some more.

The day's workout ended with a return to rag Bhairav. It began with his ruminating about the difference between knomal Re in Bhairav and komal Re in Shri.Mostly we focused on Bhairav, expecially his wild but methodical system of tan formation. But there was ian interlude (early in this clip) of his playing Miyanki Malhar ver lucidly on my sarangi. The video ends with delicious mutton curry and roti—the best I've ever tasted!

On the 30th of August, 1997, Mohammed Ali Khan focused on rag Hemant including two bandishes.

My next visit was on the 2nd of September, 1997. We bagan with rag Lalit. We were in relatiove darkness, appropriate to the early early morning time of Lalit, but the light came on after a while. As usual he taught me a couple of bandishes. At one point the Ustad drifted into demonstrating rage Lalit Pancham.

Next was rag Purvi:

And finally Bhairavi, a somewhat scattered but intersting session.

On the 5th of September we spent a long time on rag Jaijaivanti:

Then there was a somewhat scattered stream-of-consciousness segment that looked at the rare rags Jaijaivanti Bhar, and Ramkali Bahar and more.

We then went to the home of his son, Ahmed Ali to look at several interesting historical photographs: of Mohammed Ali Khan, of his father and grandfather, of Bundu Khan, and of the four great brothers, Maman Khan Kale Khan, Sughrai Khan and another Khan.

END OF 1997. PLEASE VISIT "Mohammed Ali Khan Part 2" for 1998